DISCOVER YOUR LOCAL BICYCLING COMMUNITY

Find local advocacy groups, bike shops, instructors, clubs, classes and more!

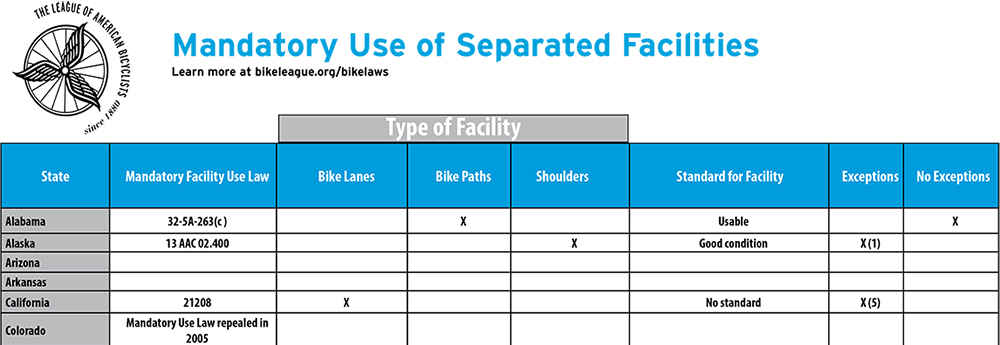

Bike Law University: Mandatory Use of Separated Facilities

Mandatory Use laws require bicyclists to use facilities that are provided or designated for their use.

Mandatory Use laws require bicyclists to use facilities that are provided or designated for their use.

These laws generally require a bicyclist to use a separated path (often referred to as a sidepath), a marked bike lane, or a roadway shoulder, rather than the parallel or adjacent travel lanes provided for motor vehicles. Some, but not all, of these laws provide a standard for the facility, allowing a bicyclist some flexibility to choose to use the roadway rather than the facility if that standard is not met.

In the 1970s, mandatory use laws of some sort existed in 38 states. Since that time many cycling advocates and state legislatures have worked together to repeal many of those laws. Today there are 17 states with some type of mandatory use law and only 11 of those states have laws that apply in most circumstances.

Why should you care?

The League believes that cyclists have a fundamental right to the road. For a great discussion of the emergence of cyclists’ right to the road and its current foundation I recommend reading the first chapter of Bob Mionske’s Bicycling and the Law. The League does not support mandatory use laws, and believes that cyclists should not be required to use dedicated bicycle facilities.

The League believes that cyclists have a fundamental right to the road.

Laws that mandate that a bicyclist use a particular facility undermine the ability of a bicyclist to protect him or herself when those facilities are not well planned, designed, and/or maintained. They may also promote unhealthy relationships between bicyclists, other road users, and law enforcement by setting authoritative rules where education and judgment might be more effective. There are numerous operational reasons why a dedicated bike facility might be rendered unsafe or impractical — such as an accumulation of debris, illegally parked vehicles, the need to make a left turn — and in such cases cyclists need to be able to ride in the adjacent or parellel travel lanes without fear of prosecution. In addition, it is difficult to design a bike lane or path that will appropriately accommodate the great diversity of bicyclists from children to professional racers and mandatory use laws fail to recognize the different needs of the many members of the cycling community.

The best way for communities to encourage bike lane and path use is to build them and build them well. There is tremendous demand and use of bike lanes and paths regardless of mandates. Building facilities that at least meet the standards developed by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) or American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) is a great way to ensure that those facilities are well built and will provide cyclists with safety and comfort. When safe, comfortable, and accessible facilities are built then most cyclists will choose to use them.

Although great progress has been made since the 1970s, mandatory use laws are still a problem, showing up in federal and state contexts. The League believes that these laws do nothing to benefit bicyclists and should be fought at every level.

Click on the image above for the full chart.

Click on the image above for the full chart.

Who has them?

Seventeen states have some law that requires, or enables localities to require, the use of a bike lane, bike path, or shoulder when that facility is present. Of those 17 states, several laws have limited applicability or effect:

- In Georgia and Utah the laws merely enable localities to enact mandatory use laws.

- In Connecticut and Kentucky the laws only require the mandatory use of a separated facility when such a facility is marked on a highway or parkway (i.e. limited access roadways).

- In Kansas the law only applies when a sidepath is dedicated to bike use only.

- In Oklahoma the law only requires the use of a bike path within parks.

After accounting for these six states that have mandatory use laws of limited applicability there are only 11 states with mandatory use laws that generally apply.

- States generally require the use of a sidepath – Alabama, Nebraska, Oregon, West Virginia

- 7 States generally require the use of a bike lane – California, Florida, Hawaii, Maryland, New York, Oregon, South Carolina

- 1 State generally requires the use of a shoulder – Alaska

Several of these states provide exceptions to their mandatory use laws to address the many situations in which strict application of the law would be unsafe or impractical. There are five common exceptions and they occur in different frequencies. The average for all states is to have slightly more than 1 exception. The most common number of exceptions for a state to have is zero.

|

Exception |

Number of States with Exception |

|

Passing |

6 out of 11 |

|

Turning to the left |

5 out of 11 |

|

Avoiding hazards or hazardous roadway conditions |

6 out of 11 |

|

Operating at or above the rate of speed of normal traffic flow on the roadway |

3 out of 11 |

|

Avoiding right hooks |

3 out of 11 |

|

No Exceptions |

5 out of 11 |

Spotlight State – Oregon

If you are a fan of bicycle lanes and paths, then you probably like Oregon. Since the 1971 “Bike Bill”, bicycle facilities have been required whenever a road, street or highway is built or rebuilt. Unfortunately, Oregon requires the use of a bicycle lane or path when one is available. While Oregon would be even better for bicycling if it had no mandatory use law, there are some notable features of Oregon’s mandatory use law which are an improvement upon more common mandatory use laws.

Oregon’s law has:

- A relatively strong standard for the quality of bike facilities: Oregon’s mandatory use law requires that a bicycle path or lane be “suitable for safe bicycle use at reasonable rates of speed.” This standard does not adopt a specific national facility standard, like those created by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) or American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO). Newer standards, especially those put forward by NACTO do a very good job of making it likely bike lanes built to that standard are “suitable for safe bicycle use at reasonable rates of speed.” While standards are a great start they may not encompass all factors that are important to local cycling communities and an open standard allows other evidence regarding the suitability of the path or lane to be considered.

- A public process for review of bike facilities: Oregon’s mandatory use law requires a “public hearing” regarding whether bicycle facilities meet the standard of “suitable for safe bicycle use at reasonable rates of speed” before a citizen can be cited for violation of the law. The extent of the public hearing is not defined. Portland has argued that the public hearing process regarding its Bicycle Master Plan is sufficient. Other localities have used City Council hearings.

- Several exceptions to the requirement of mandatory use: Oregon’s mandatory use law has five exceptions that mirror the exceptions seen in many far to the right laws. One exception worth particular note is that a bicyclist can move out of a bicycle lane or path if they are continuing straight through an intersection and the lane or path is to the right of a lane from which a motor vehicle must turn right, allowing cyclists to prevent right hook collisions.

It is also worth mentioning that in some states local jurisdictions may enact mandatory use laws. Iowa’s State Attorney General recently issued an opinion that local mandatory use laws conflict with Iowa’s state traffic law. If your state has not issued an opinion on the subject it may be worthwhile to look at that opinion and see if similar reasoning may apply in your state to preclude local mandatory use laws.

Where did they come from?

In 1944 §11-1205(c) was added to the Uniform Vehicle Code (UVC) and contained a mandatory sidepath provision. By 1979, only 12 states did not have a law similar to the mandatory sidepath provision set out in §11-1205(c). In 1979, §11-1205(c) was eliminated from the UVC and now only 17 states retain some version of a mandatory use law. As of the last revision to the UVC in 2000, there is no UVC sections equivalent to either a mandatory bike path or bike lane use law.