DISCOVER YOUR LOCAL BICYCLING COMMUNITY

Find local advocacy groups, bike shops, instructors, clubs, classes and more!

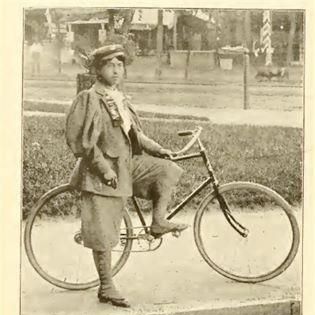

Women’s (Bike) History: Kittie Knox

There was no denying that Miss Kittie Knox was a card-carrying member of the League of American Wheelmen, but her attendance at the annual meeting in 1895 lit a fire that sparked newspaper headlines from coast to coast. Only 21 years old at the time, the bi-racial seamstress and cycling enthusiast dared to challenge the new “color bar” instituted by the League just one year earlier.

There was no denying that Miss Kittie Knox was a card-carrying member of the League of American Wheelmen, but her attendance at the annual meeting in 1895 lit a fire that sparked newspaper headlines from coast to coast. Only 21 years old at the time, the bi-racial seamstress and cycling enthusiast dared to challenge the new “color bar” instituted by the League just one year earlier.

Even before the controversy at the 1895 meeting, Knox had made a name for herself in her hometown of Boston. In 1893, the Riverside Cycling Club became the first black cycling group and, according to historian Lorenz Finison, Knox was among a “small coterie of black women cyclists in the early part of Boston’s [bicycling] craze.” In 1893, the Indianapolis Freemen, a black newspaper of the time, reported on Knox and Viola Wheaton performing “graceful” cycling at a meet-up in Martha’s Vineyard. That same year, Knox was listed in the rolls of the Bulletin — the League’s newsletter of the time — as a member of the growing ranks of the Wheelmen. But controversy was brewing… In 1894, despite strong opposition from many local affiliates, including numerous cycling clubs in Boston, the League passed a color bar. Spearheaded by Colonel W.W. Watts from Louisville, Ky., it was resolved at the annual meeting in 1894 that “none but white persons can become members of the League.” Since Knox was already a card carrying member — one of just a few hundred women at the time — it set the stage for an possible showdown at the 1895 meeting. But Knox wasn’t one to shy away from the spotlight. In fact, in the run-up to the League’s annual meeting, she pushed the boundaries of women’s dress, winning a July 4th costume contest at the Waltham Cycle Park — clad in a gray knickerbocker suit. “Knickerbockers referred to what had been typical men’s and boy’s baggy trousers,” Finison writes in his upcoming book. “That Kittie won with such a uniform was quite astounding, and a testament to her seamstress skills, given the animus in some quarters against women of the time wearing anything but skirts – and long skirts at that.” Knox must have been prepared for some animus from members when she joined thousands of cyclists in Asbury Park to participate in the League Meet. What happened when she arrived isn’t entirely clear. Some newspapers described Knox being refused entry — and either withdrawing quietly or walking out defiantly — while other reports denied her exclusion. As Finison describes it:

[Knox] was entering a socially segregated space – the Asbury Park hotel district, and given recent history, she must have known the controversy her appearance might create. However, she had the support of her Boston cycling companions, and her entrance was featured in many of the national and local newspapers, which seemed to regard her as a full member of the Boston cycling contingent, despite the existence of the color bar. The New York Times reported: “With the Boston delegation is also Miss Kittie Knox, a pretty young colored girl, who rides in the Riverside Cycle Club, Boston’s only colored cycle club.” The Times got quickly to the heart of the conflict: “This afternoon Miss Knox did a few fancy cuts in front of the clubhouse and was requested to desist. It is thought that this episode will result in temporarily opening the color line question. Some of the Asbury Park wheelmen officials, it is said, will protest against permitting Miss Knox to remain a member of the league… [and] the local ‘kickers’ say they will have a reckoning with the League Secretary, Abbot Bassett, upon his arrival.”

Far-off newspapers such as the San Francisco Call described the uproar: “When Miss Knox, whose appearance and dress had been objects of admiration all day, walked into the committee-room at the local clubhouse and presented her League card for a credential badge the gentleman in charge refused to recognize the card, and the young woman withdrew very quietly. Ninety-nine out of every hundred members interviewed express the heartiest sympathy for her and condemnation of the hasty action of the badge committee.”

The Boston Herald denied her ouster from the Meet when Asbury Park officials resisted her entrance to the clubhouse and “refused to grant her the privileges offered to every dollar-per-year member of the league.” “… a good angel appeared in the person of Mr. Robinson of the Press Cycling Club, who secured for her the desired badge.” The Morning Express of Buffalo concurred: “Miss Katie Knox, negress, the young woman rider from Boston, who had been a member of the L.A.W. for the past six years, denies the sensational reports that were sent out last evening regarding her… Miss Knox says that she has no complaints to make concerning her reception from the local wheelmen, and is greatly annoyed by the publicity given to the alleged unpleasantness.”

Either way, Knox was a true pioneer, sparking a public debate of the color bar and exerting her right to be recognized and admitted as a member of the League. Several weeks later, her presence pushed the League to confront the issue in its Bulletin. “Can a negro be a member of the L.A.W.” a member asked, “as it appears Miss Knox of Boston is?” In response, the League explained: “Miss Katie J. Knox joined the League, April 1, 1893. The word ‘white’ was put into the constitution, Feb. 20, 1894. Such laws are not and cannot be retroactive.”

The color bar would remain a little-known relic of League history, until it was publicly repudiated in 1999. Tragically, Knox died just a few years later in 1900, but, as Finison writes in his upcoming book: “The issues of race and gender were thrust into the national spotlight, and while Kittie had hardly been received with open arms, she had achieved, with her courage and stylish outfits, an unprecedented level of celebrity.”

Stay tuned for more women’s bike history next week!