DISCOVER YOUR LOCAL BICYCLING COMMUNITY

Find local advocacy groups, bike shops, instructors, clubs, classes and more!

Guest Post: Who Does Biking Serve?

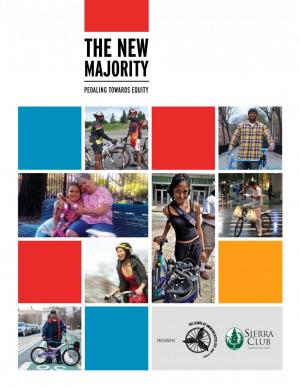

Last month, in partnership with the Sierra Club, the League released “The New Majority: Pedaling Toward Equity.” A conversation-starter, rather than a comprehensive analysis, the mini-report highlighted the growth in bicycling among youth, women and people of color — and showcased the stories of just a few grassroots organizations that are mobilizing diverse communities and elevating new leaders.

As we hoped, the report has indeed sparked discussion, including a thought-provoking post on Surly Urbanism. The author, Jamaal Green is a PhD student in Urban Studies and Planning at Portland State University and has a masters in city and regional planning from UNC-Chapel Hill, specializing in economic development and researching broadly in the areas of planning for social justice and equity. With his permission, we’re cross-posting his thoughts on the Bike League Blog, as well.

The urbanist/planning internet world has been taken over by the recent activation of NYC’s bikeshare program, Citi Bike. Folks on Twitter breathlessly report growing enrollment and already are asking if it is time to expand the system. Tweets, blog posts, and articles in traditional media have explored this new system in a staggering amount of ways, ranging from the snarkily celebratory, to considered technical critiques, to outright wingnuttery.

The urbanist/planning internet world has been taken over by the recent activation of NYC’s bikeshare program, Citi Bike. Folks on Twitter breathlessly report growing enrollment and already are asking if it is time to expand the system. Tweets, blog posts, and articles in traditional media have explored this new system in a staggering amount of ways, ranging from the snarkily celebratory, to considered technical critiques, to outright wingnuttery.

More recently, though, a new discussion point concerning bike share programs and cycling, in general, has arisen: “What do we do about poor people and people of color?”

The relationship between cycling and poor and minority communities is one that is simultaneously simple and complex. A recent report from the League of American Bicyclists and the Sierra Club, covered in Atlantic Cities here, shows some numbers that challenge the “racial stereotype” of cyclists in America. This report has spurred even more commentary, again from Atlantic Cities, on how communities of color and low-income communities are not well served by “cycling’s egalitarian aspirations.”

Bike share programs are the perfect targets for these columnists and thinkers to express their racial and class anxiety concerning the fraught relationship that many cycling advocacy organizations have with these communities. Commentators accurately point out that the lack of infrastructure is a major impediment to getting low income communities excited about cycling and recent attention paid to the continued “suburbanization of poverty” speaks to a major spatial mismatch between those communities that could be best helped by safe bicycling infrastructure and programs or services designed to help folks bike.

But where these commentators fall short is that they assume that this situation has just “developed” naturally over time, as opposed to being the result of a series of deliberate, considered political decisions. So, the questions surrounding cycling and communities commonly perceived to be disinterested in cycling often end up being some distillation of, “How do we get poor/POC onto bikes/using [insert corporate bikeshare name]?” When the question really should be, “What do these communities need/want?”

And this is my point/theory: Cycling’s growing popularity over the past decade or so is due to the fact that a preferred demographic has pushed for it. I had an extended conversation on Twitter the other day around this idea where I semi-jokingly said that the forces that destroyed black and poor neighborhoods with highway construction from the 40s to the 60s are the same ones now pushing bike lanes. There are clear differences: Urban renewal was a federally funded program (though locally controlled and the identification of “blighted” areas was often a pure racial clearance project) and transparently “elite” driven. Highways to downtowns were built in a vain attempt to draw new suburban residents back into cities to shop and work. We know the general story, segregated suburbanization continued uninhibited for decades, exacerbating sprawl, accelerating the disinvestment of central cities and intensified ghettoization.

But isn’t everything different now? Young, “creatives” flock to central cities to work in high-tech firms and to enjoy the culture of cities in opposition to the banality of suburban living. And they bike! How is this bad?

Well, it’s not a bad thing. But we need to step back and ask whose interests are being served. The return to the city of these folks is largely based on long campaigns of displacement and gentrification. Neighborhoods that were left to rot for decades are now sites of “revitalization” and are seeing the rise of new commercial services, infrastructure, and attention from city officials. But these are also the same neighborhoods that have asked for better transit service, safer streets, better schools, and opportunities to develop community-serving businesses for decades and generally have been ignored. And yes, even these neighborhoods before the influx of new gentrifiers had people who cycled, but it was never the goal of the city to support these small, poor cyclists with essential infrastructure or to even encourage the activity in poorer neighborhoods. We can blame some of this on a “car culture” and bicycle stigmatization, but as Grabar’s piece correctly points out, these areas have always been underserved.

Succinctly, the same forces that sought to serve elite interests and encourage redevelopment of center cities through highway construction are the same ones that now see bikes, and their attendant infrastructure, as a way to spur redevelopment and to attract a new preferred class. Any statement from a mayor or urbanist commentator that speaks about bike lanes as a way to attract young professionals is part of this plan. It’s simply the new infrastructure du jour designed to steer capital into formerly disinvested areas.

This does not mean that bike lanes cause gentrification or that you can’t build bike infrastructure anywhere for fear of displacement. But we should take a step back and truly ask, “Who are we serving?” and, “Why are we building?” It is telling and sad that we can recognize the spatial switch of our regions, now with more wealthy centers and poorer suburbs (a great adaption of the European model), and yet still puzzle over a lack of enthusiasm on the part of poorer neighborhoods and individuals for bikes. People aren’t stupid. They know that their cities rarely, if ever, do anything to actually help them and the past two decades, in many areas, have seen nothing but a race for cities to accelerate displacement through selective investments in formerly disinvested neighborhoods. Bike lanes are just yet another indicator of a city building something for a potential inhabitant rather than the folks already there.

To conclude, ask yourself about any plan or project: “Who does this serve? Why are we doing it? Who wins? Who loses? Who pays for it?”