DISCOVER YOUR LOCAL BICYCLING COMMUNITY

Find local advocacy groups, bike shops, instructors, clubs, classes and more!

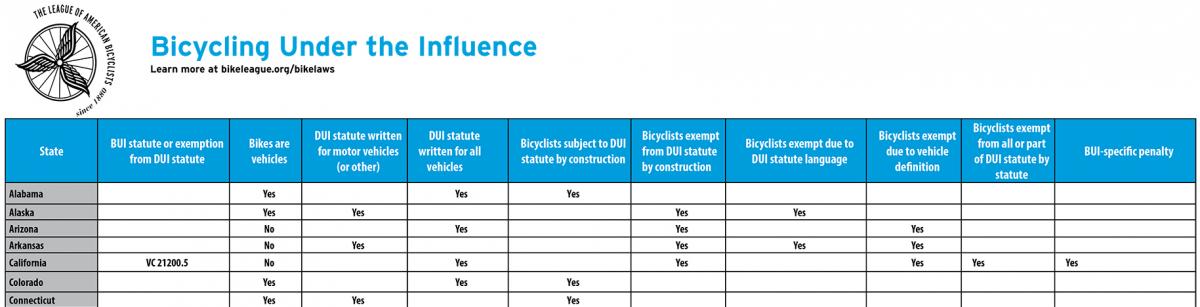

Bike Law University: Riding Under the Influence

Bicycling under the influence laws are very rare, often times leaving a gray area in the law.

In this edition of Bike Law University, we take a look at BUI laws and how they’re implemented across the country. BUI laws provide specific penalties for bicyclists that are found to be riding while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. In most cases, BUI laws differ from Driving Under the Influence (DUI) laws by providing for less severe penalties and by not affecting a person’s driver’s license.

What are they?

When determining whether bicyclists are likely to be subject to DUI laws I used the following process:

1. Is there a bicycle-specific DUI-like statute? When there is a BUI statute that law will likely govern how intoxicated cyclists are treated, unless law enforcement officers choose to use more general public intoxication laws or the statute does not clearly prevent the DUI law from applying.

2. Is a bicycle a vehicle? Although bicycles are always given the rights and duties of vehicles, they are not always actually defined as vehicles. It is important to look at the vehicle definition in the state code in addition to the definition of bicycle.

3. Is the DUI statute written for all vehicles? Because the definition for vehicle is often very broad, DUI statutes are sometimes written for motor vehicles, rather than vehicles generally. In some states, the DUI law will alternatively specifically exclude vehicles moved solely by human power or provide for some other altered definition that more specifically targets motor vehicles.

4. Is there case law on the subject in this state? In my search of Google Scholar I found 18 states that have case law on the applicability of their DUI law to the bicyclists. The case law generally centers on two areas of interest: 1) whether bicyclists are by their nature exempt from all or part of the DUI law, and 2) whether the statutory language and intent precludes the application of the DUI law to bicyclists.

5. What is the most likely outcome of litigation on this subject if the law is not clear?In states that do not have case law on the subject, or where the only decisions are by lower level courts and are not definitive, I looked at the trends in interpretation by courts in other states. These trends of interpretation will be discussed below.

Click on the image for the full chart.

Click on the image for the full chart.

Why should you care?

There are several studies that support the idea that BUI is a safety problem, and specifically that “[a]lcohol-intoxicated riders are considerably more likely than sober cyclists to be severely injured or killed.” According to Peter Jacobsen and Harry Rutter in City Cycling, “[i]n one study in Portland, Oregon, although only 15 percent of killed and hospitalized adult cyclists had elevated blood alcohol levels, half of the adult cyclists with fatal injuries were intoxicated (Frank et al. 1995).” In another study: “Of 200 injured cyclists reviewed during a study at a regional trauma center in Austin, Texas, 40 either had measurably elevated blood alcohol levels or themselves reported having consumed alcohol.

The intoxicated cyclists were much more likely to have been injured at night or in the rain and to have been admitted to the hospital. Only 1 of the 40 (2.5%) alcohol-consuming cyclists had worn a helmet, compared to 44 percent of the others. Both cyclists who incurred severe brain injuries were intoxicated, and the average hospital care cost of the alcohol-consuming cyclists was twice that of their sober counterparts. (Crocker et al. 2010).” Beyond the dangers caused by alcohol intoxication, it seems likely that intoxication is associated with behaviors that otherwise increase the risks of injury while bicycling such as riding without a helmet, riding at night, and riding without proper reflective gear or lights.

That intoxicated cyclists are overrepresented amongst cycling fatalities should not be confused with the idea that BUI is a widespread problem within the bicycling community or that its reduction will dramatically improve roadway safety. Although, the mixing of bicycling culture and beer culture can be seen in many examples, from breweries organizing bike-themed festivals to bicycle concepts built around transporting beer, and, in some cases, bicycles are the transportation choice of persons who have lost their driver’s licenses due to DUI, there is little evidence to suggest that BUI is common. The evidence that does exist suggests that BUI is less common than other forms of intoxicated transportation.

In City Cycling, a study of over 1,000 traffic fatalities in England and Wales found that “of all road users killed … cyclists were the least likely to have consumed alcohol or drugs. Of the cyclists tested, 33 percent showed the presence of alcohol and/or drugs, compared to 55 percent of drivers, 52 percent of car passengers, 48 percent of motorcyclists, and 63 percent of pedestrians (Elliot, Woolacott, and Braithwaite 2009).” In addition, “More cyclists fatalities are due to intoxicated motorists than intoxicated cyclists (Kim et al. 2007).”

Doing a better job of recognizing and dealing with BUI can be part of a road safety agenda, but our current legal system does not seem to be equipped to deal with the issue. To be taken seriously as road users, with the same rights and responsibilities as the operators of motor vehicles, means that cyclists should avoid BUI. However, the potential harm of BUI is not readily comparable to the well documented dangers of DUI. The normalization of bicycles as a legitimate transportation mode does not mean that bicyclists should be fit into the pre-existing framework for motor vehicles, but that they should be treated with the same seriousness. BUI and DUI are separate public policy issues that deserve separate public policy responses.

Who has them?

Four states have BUI statutes that provide specific penalties for bicyclists found riding under the influence. In five states a statute exempts bicyclists from all or part of the state DUI statute. In the remaining 41 states the application of the state’s DUI laws may be unclear, unless controlling case law exists.In 24 other states, there is some reason to believe, based upon the language of the DUI statute, definition of a vehicle, or the interaction of the two, that the DUI law does not apply to bicyclists. In these states a bicyclist may still get in serious trouble for BUI, but it is likely that a bicyclist will be cited with another statute, such as disorderly conduct or drunk in public. In the remaining 21 states, and the District of Columbia, it is likely that bicyclists can be charged with DUI based upon the reasoning laid out previously in this post.

Where did they come from?

Driving under the influence is addressed in the Uniform Vehicle Code (UVC) in §11-902. There is no Bicycling under the influence equivalent, however applying the reasoning discussed previously to the UVC (esp. §§1-215, 1-109, 11-1202, and 11-902), bicyclists would likely be subject to the UVC’s DUI provisions.

Spotlight State: Washington

In Washington, a bicycle is defined as a vehicle and the DUI law applies to all vehicles. In most states with similar language courts have found the DUI law to apply to bicycles. However, in 1995, the Division 2 Court of Appeals of Washington in Montesano v. Wells, 902 P.2d 1266 (1995), held that Washington State’s DUI law was meant to apply only to motor vehicles. Since this decision Washington State passed new legislation on the subject of bicycling under the influence (BUI). This new legislation deals with the safety issues that BUI can cause for cyclists, but minimizes the punishment for BUI.

“(1) A law enforcement officer may offer to transport a bicycle rider who appears to be under the influence of alcohol or any drug and who is walking or moving along or within the right-of-way of a public roadway, unless the bicycle rider is to be taken into protective custody under RCW 70.96A.120. The law enforcement officer offering to transport an intoxicated bicycle rider under this section shall:

(a) Transport the intoxicated bicycle rider to a safe place; or

(b) Release the intoxicated bicycle rider to a competent person.

(2) The law enforcement officer shall not provide the assistance offered if the bicycle rider refuses to accept it. No suit or action may be commenced or prosecuted against the law enforcement officer, law enforcement agency, the state of Washington, or any political subdivision of the state for any act resulting from the refusal of the bicycle rider to accept this assistance.

(3) The law enforcement officer may impound the bicycle operated by an intoxicated bicycle rider if the officer determines that impoundment is necessary to reduce a threat to public safety, and there are no reasonable alternatives to impoundment. The bicyclist will be given a written notice of when and where the impounded bicycle may be reclaimed. The bicycle may be reclaimed by the bicycle rider when the bicycle rider no longer appears to be intoxicated, or by an individual who can establish ownership of the bicycle. The bicycle must be returned without payment of a fee. If the bicycle is not reclaimed within thirty days, it will be subject to sale or disposal consistent with agency procedures.”

This law does not give cyclists a free pass, or turn the police into their taxi service, but rather provides for a way to get intoxicated cyclists and pedestrians away from streets where they may be in danger without invoking harsh penalties meant for intoxicated drivers or more general laws related to the disruption that may be caused by an intoxicated person in public. What the law does is recognize that intoxicated cyclists, and pedestrians, are likely to primarily endanger themselves and that there is a public interest in protecting them.

Case Law Trends

Where bicycles are vehicles, and the DUI statute is written for all vehicles, courts overwhelmingly find that the DUI statute applies to bicycles.

- This has been found in the District of Columbia [Everton v. DC, 993 A.2d 595 at 596-7 (2010)], Florida [State v. Howard, 510 So.2d 612 (1987)], North Dakota [Lincoln v. Johnston, 2012 ND 139 (2012)], Ohio [Ohio v. Hilderbrand, 40 Ohio App. 3d 42 (1987)], Oregon [State v. Woodruff, 726 P.2d 396 (1986)], Pennsylvania [Commonwealth v. Sheriff, 7 Pa. D. & C. 4th 201 (1990); Commonwealth v. Brown, 423 Pa. Superior Ct. 264 (1993)], and South Dakota [State v. Bordeaux, 710 N.W. 2d 169 (2006), the law has since been amended]. In each case, although the number and complexity of the statutes involve varies, the plain language of the statutes meant that bicycles were vehicles and the DUI law applied to all vehicles.

- However, in Washington [Montesano v. Wells, 902 P.2d 1266 (1995)], the court found that although “a literal reading … appears to allow the state to charge bicyclists with driving under the influence” the legislature did not intend such application. The court reached this finding because the definition of vehicle was only recently amended to include bicycles, and the DUI statute was not amended to address this new definition. The court found it particularly persuasive that the DUI statute used vehicle and motor vehicle interchangeably in a way that would have made bicyclists subject to DUI but not subject to a lesser included offense, and that such application would be absurd. Additionally, public policy considerations that informed the DUI law, the extreme danger inherent in motor vehicles, did not weigh in favor of applying the DUI law to bicycles.

2. Where bicycles are vehicles, and the DUI statute is written for anything other than all vehicles, it is less clear that a court will apply the DUI statute to bicycles.

- In Louisiana [State v. Carr, 761 So.2d 1271 (2000)], the Louisiana Supreme Court found that there was an ambiguity in the larger statute of which their DUI was part that suggested two reasonable interpretations where “other means of conveyance” could mean motorized or non-motorized conveyances. Due to this ambiguity, the principle of lenity – that ambiguous criminal statutes should be strictly construed in favor of the defendant to ensure that they provide fair warning of what is criminal, led the court to conclude that a bicycle was not an “other means of conveyance.

3. Where bicycles are not vehicles, courts are unlikely to find that the DUI statute applies to bicycles

- This has been the case in California [Clingenpeel v. Municipal Court, 108 Cal.App.3d 394 (1980)], Illinois [People v. Schaefer, 654 N.E.2d 267 (1995)], Kansas [City of Wichita v. Hackett, 275 Kan. 848 (2003)], and Michigan [Hullett v. Smiedendorf, 52 F. Supp. 2d 817 (1999)].

i. These cases generally follow a similar pattern:

- The State argues that their statute based on UVC 11-1202 [“Every person propelling a vehicle by human power or riding a bicycle shall have all of the rights and all of the duties applicable to the driver of any other vehicle under chapters 10 [accidents and accident reporting] and 11 [rules of the road], except as to special regulations in this article and except as to those provisions which by their nature can have no application.”], persons on bicycles are subject to the DUI law because they are subject to all of the duties applicable to the driver of a vehicle.

- The Court finds ambiguity in the statute based on UVC 11-1202 because it would be reasonable to interpret that either: 1. Bicycles are not vehicles – and the plain language of the DUI laws only applies to vehicles – therefore the state’s DUI laws by their nature do not apply to bicycles. 2. The state’s version of UVC 11-1202 subjects bicyclists to the same duties applicable to drivers of vehicles – and therefore bicyclists should be subject to the DUI laws.

- The Court finds that the ambiguity makes it so that the laws do not inform cyclists that they are liable to punishment for driving a bicycle while under the influence in terms sufficiently clear that men of common intelligence would not differ as to its application, and therefore the laws do not subject bicyclists to criminal sanctions.

- The Court may supplement its textual reasoning with public policy arguments based upon the smaller threat to the public due to intoxicated bicyclists, as when the Court in Clingenpeel said “[p]eople of common intelligence would not assume that [DUI punishment] was intended to be made applicable to drunk driving of bicycles, to which it would appear to be an overkill” because “the combination of bicycle and cyclist does not possess the “great force and speed nor is it capable of producing the carnage and slaughter reaching the astounding figures only heard of on the battlefield (citations omitted).”

4. Where all or part of a DUI statute uses “motor vehicle”, courts are unlikely to find that section applies to bicycles

- This has been the case in DUI cases in New Jersey [State v. Machuzak, 227 N.J. Super. 279 (1988); State v. Johnson, 203 N.J. Super. 436 (1985)] and by analogy in New York [People v. Szymanski, 63 Misc.2d 40 (1970)]. In addition, in Oregon [State v. Woodruff, 726 P.2d 396 (1986)] and Pennsylvania [Commonwealth v. Sheriff, 7 Pa. D. & C. 4th 201 (1990)] found that implied consent laws did not apply because those laws used “motor vehicle” rather than “vehicle.” In these cases, the courts generally find that the plain language of the statutes mean that they do not apply to bicyclists or other persons who do not fall within the definition of “motor vehicle.” Because the legislature chose to categorize vehicles differently (motor vehicles vs. other vehicles), the courts commonly say that it is the responsibility of the legislature to resolve the ambiguity of the DUI laws application to bicyclists. In New York, the Szymanski case dealt with a horse-drawn carriage but the court noted that identical language dealt with persons riding bicycles and the same logic applied.

- However, there is a split amongst New Jersey trial courts and State v. Tehan, 190 N.J. Super. 348 (1982) found that the state’s DUI law could be applied to bicyclists, but the bicyclist could not have their license suspended even though the DUI law did apply. This decision is criticized in the later cases from New Jersey as giving greater effect to the statute than the statute’s language requires and ignoring the DUI law’s more specific language when applying the language that gives a person on a bicycle the duties of the driver of a vehicle. Since all three cases are the decisions of trial courts, none of the cases are determinative of how the DUI law will be applied in New Jersey.

5. Courts do not generally find that DUI laws are the type of duty that by its nature cannot apply to a person riding a bicycle.

- While there are instances of bicyclists being held exempt from rules of the road due to the different natures of bicycles and other vehicles (according to a New York State Appellate Court, Secor v. Kohl, 67 A.D.2d 358 at 362-3 (1979), bicyclists are exempt from signaling continuously for the same number of feet as a car, because that requirement was based upon the speed at which a car travels), courts generally rely upon the plain language of the statutes or overall the intent of the legislative scheme rather than looking at the nature of bicycles and other vehicles and the public policy reasons for prohibiting the intoxicated operation of different vehicle types. An exception is the New Jersey case, Tehan, where the court found that because bicycling is an unlicensed activity the license forfeiture provisions of the DUI law could not require that defendant forfeit his right to operate his bicycle on the roads.

The discussion above hopefully helps you to understand whether or not your state has confronted the issue and whether it has done so in an appropriate manner. As bicycling becomes more popular instances of BUI are likely to increase and there is likely to be renewed interest in enforcing DUI laws against bicyclists. The bicycling community should be ready to talk about the real safety issues caused by BUI, but it is entirely appropriate to consider, as many courts already have, the vast difference in the threat to public safety caused by intoxicated bicyclist vs. intoxicated motor vehicle drivers. Our understanding of the danger that it poses, both to bicyclists and to the public generally, is limited because of the general lack of bicycle accident data but it is hard to believe that it approaches the severity of DUI. As others have argued, I think that BUI should be recognized as a distinct public policy issue that deserves its own solution, rather than shoehorned into our DUI laws.