Posts by Ken McLeod

Bike Law University: Where to Ride Laws

Bicyclists have been fighting for good roads and the right to use them since before the League of American Bicyclists was founded in 1880. Where to Ride laws strike at the very heart of advocacy: Bicyclists’ right to the road. When safety requires a bicyclist to take the lane, it is important that the law allows a bicyclist to do so.

In this edition of Bike Law University, we take a look at Where to Ride laws and how they have shaped bicyclists safety.

What are they?

Where to Ride laws tell bicycles, or vehicles generally, how they should position themselves on the road. These laws create and manage the expectations of road users regarding the behavior of others while traveling on the road. In most states, the law that applies to bicyclists regarding road position starts with a variation of requiring a position as far to the right as practicable.

When you talk about Where to Ride laws it is necessary to begin by defining the word practicable. In most states a bicyclist is required by law to ride as far to the right as practicable, sometimes referred to as AFRAP. The obvious and necessary question to a bicyclist seeking to comply with the law, motorists judging bicyclist behavior, and law enforcement officials tasked with enforcing the law is – what does practicable mean? So, inevitably a dictionary is consulted and we learn that it means “capable of being put into practice,” which is likely to mean one thing to an experienced road cyclist, one thing to a driver who is annoyed at a “law breaking” cyclist safely taking the lane, and a different thing to every law enforcement officer who by order or inclination enforces the law. What is practicable is often context sensitive based upon road and traffic conditions. The League generally recommends that cyclists ride in the right third of the lane with traffic.

Click here to see the full chart.

Cyclists and police at times disagree over where on the road cyclists can ride. Cyclists have successfully fought tickets issued under Where to Ride statutes based upon exceptions in the law, including narrow lanes and hazards. Local bicycling advocates and League Certified Instructors can be valuable resources if you are ever prosecuted under a Where to Ride law. If a disagreement occurs, it may be useful to consult bicycle safety education materials and roadway design manuals. In addition, sharrows, where marked, are usually meant to serve as an indication of where to ride and can be used as an insight into official ideas of what is “practicable.”

Bike Law University: Distracted Driving

April is National Distracted Driving Awareness Month and there are numerous national, state, and local campaigns to educate the public about the dangers of not putting down your cell phone…

Read MoreBike Law University: Vulnerable Road User Laws

The “Vulnerable Road User” concept is a new and powerful tool — and it’s taking root throughout the country.

Recent legislative successes include the “Access to Justice for Bicyclists Act of 2012” in Washington D.C., the recent endorsement of a vulnerable user ordinance by the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors (read more about that campaign here) and a statewide law in Utah. While VRU protections have proliferated in the past five years, they continue to take many shapes.

So, in this edition of Bike Law University, we explore the current laws and the concept behind them.

What are they?

Automobiles provide a shell of protection for their users — creating a safety disparity between cars and other road users. This is not to say non-automobile forms of transportation aren’t safe, but simply that there is a difference between what occurs when a car is hit at 25 miles-per-hour and what occurs when a pedestrian is hit at 25 mph. While the percentage of motorist deaths has fallen, the percentage of road fatalities that are bicyclists and pedestrians has grown in recent years (from 12 percent to 16 percent).

Vulnerable Road User laws increase protection for bicyclists and other road users who are not in cars. They are relatively new and states have chosen to protect vulnerable road users in a variety of ways. This includes usually involves 1) harsher penalties for the violation of existing laws when that violation impacts a defined set of road users or 2) the creation of new laws that prohibit certain actions directed at a defined set of road users.

Click the image above for the full chart.

Why should you care?

Safety: The vast majority of VRU laws provide for increased fines or civil liability in cases where a vulnerable road user is injured or killed because of negligence or as the result of a traffic violation. These laws increase the cost of unsafe practices that impact bicyclists and provide an incentive for safer driving practices, especially around cyclists and pedestrians. In this way the laws are much like increased fines in work zones, which promote construction worker safety. VRU laws recognize that the type of simple negligence or traffic violations that may result in minor collisions between cars can have disproportionately severe results when a vulnerable road user is involved and provide ways to address those divergent results.

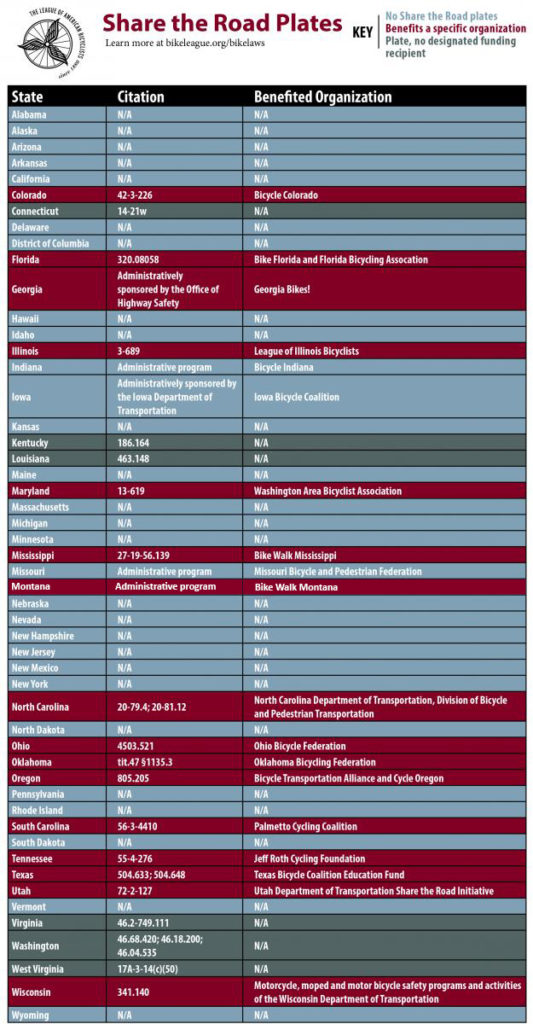

Read MoreBike Law University: Share the Road License Plates

Last week, more than 750 bicyclists from all 50 states gathered for the 2013 National Bike Summit — and several advocates were able to attend specifically because of their state’s Share the Road license plate. As a beneficiary of the specialty plates, Georgia Bikes used some of it funding to provide scholarships for three key advocates working in underrepresented communities. But the Peach State is one of two dozen that have some version of a Share the Road plate. In this edition of Bike Law University, we explore the what, why and where of this increasingly important funding source.

Read MoreBike Law University: Helmet Mandate Laws Thornier Than They Seem

It’s all the buzz for bicyclists here in the capital region: The state of Maryland could be the first to pass a law mandating helmet use for all bicyclists regardless of age.

Currently, no state has such a requirement, though a good number have a similar statute to Maryland’s: mandating helmet use for bicyclists under the age of 16.

With all the discussion about helmet laws, I figured it was a good time to tackle this thorny issue in my ongoing Bike Law University series…

What are helmet laws?

Helmet laws require any person on a bicycle wear a helmet. All current helmet laws are directed at persons under the age of 18. No state requires mandatory helmet use by all bicyclists. In many states, helmet laws can be enforced against the person on the bicycle or against a parent of that person. Some states with a mandatory helmet use law limit whether compliance with the law can be considered in civil lawsuits in order to prevent their laws from limiting the recovery of bicyclists who are injured. There are many other variations on the enforcement and effect of mandatory helmet use laws, as discussed through the laws of our spotlight states.

Why should you care?

The use of helmets is perhaps the most common recommendation for safer bicycling. The League has encouraged bicyclists to wear helmets for more than 25 years, and our affiliated clubs and advocacy groups typically require their use on organized rides. However, the League does not support mandatory helmet laws because of the many potential unintended consequences.

The experience of countries with greater bicycle use than the United States tells us that safer bicycling comes from many policy decisions — especially safer infrastructure — and does not require mandatory helmet use laws. Mandatory helmet use laws may hurt bicyclist safety overall by discouraging bicycling, by promoting the idea that it is an unsafe activity or by raising a barrier to transportation choice — despite being the safest choice for an individual cyclist. We all want safer bicycling and policies that encourage more people to ride, provide appropriate facilities, and educate all road users about safely sharing the road. These are likely to be more effective in the long term.

Who has them?

Twenty-one states and the District of Columbia have laws that require persons under the age of 18 to wear a helmet. Within that, however, the age threshold varies widely. Of states that require helmet use, most (12) only require helmets for persons less than 16 years of age. Of the 15 states that require helmet use, the District of Columbia and Virginia — which does not require helmet use — maintain a law that limits the consideration of failure to wear a helmet in a lawsuit. This protects the ability of a bicyclist who chose not to wear a helmet to recover damages if they are injured in a crash. The need for and effect of such a law may be more or less necessary depending upon how liability or fault is determined in a state.

(Click on the image to view the full chart showing the breakdown of helmet laws across the country.)

Where did they come from?

The first state to pass a mandatory helmet law was California in 1986. The Consumer Product Safety Commission has had mandatory helmet performance requirements for helmet manufacturers since 1999. As of the last revision to the Uniform Vehicle Code (UVC) in 2000, there is no UVC section equivalent to a helmet law.

Spotlight States – New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania

Read MoreBike Law University: Summary of State Safe Passing Laws

A few weeks ago we launched our state-specific highlights of traffic laws that affect bicyclists — and the feedback was tremendous. We know you’re keen to learn more, so, over…

Read MoreWhat’s at the Intersection of Transportation and Technology?

What lies at the intersection of transportation and technology? In a word: TransportationCamp. Put on by OpenPlans, I attended the most recent event last weekend in Washington, D.C., which brought…

Read MoreLeague Takes the Lead on Bike Laws

You know the rules of the road when you’re out riding. Maybe you even teach bike skills as a League Cycling Instructor. But do you know all the bicycling laws…

Read MoreBikeyface Cartoon Illustrates Traffic Laws

You know the rules of the road when you’re out riding. Maybe you even teach bike skills as a League Cycling Instructor. But do you know all the bicycling laws…

Read MoreSonoma County Ordinance Aims to “Increase Access to Justice” for Bicyclists

The Sonoma County Bicycle Coalition (SCBC) has responded to an incident of road rage by focusing attention on bicyclist harassment and working to pass an ordinance to protect harassed bicyclists.…

Read More