DISCOVER YOUR LOCAL BICYCLING COMMUNITY

Find local advocacy groups, bike shops, instructors, clubs, classes and more!

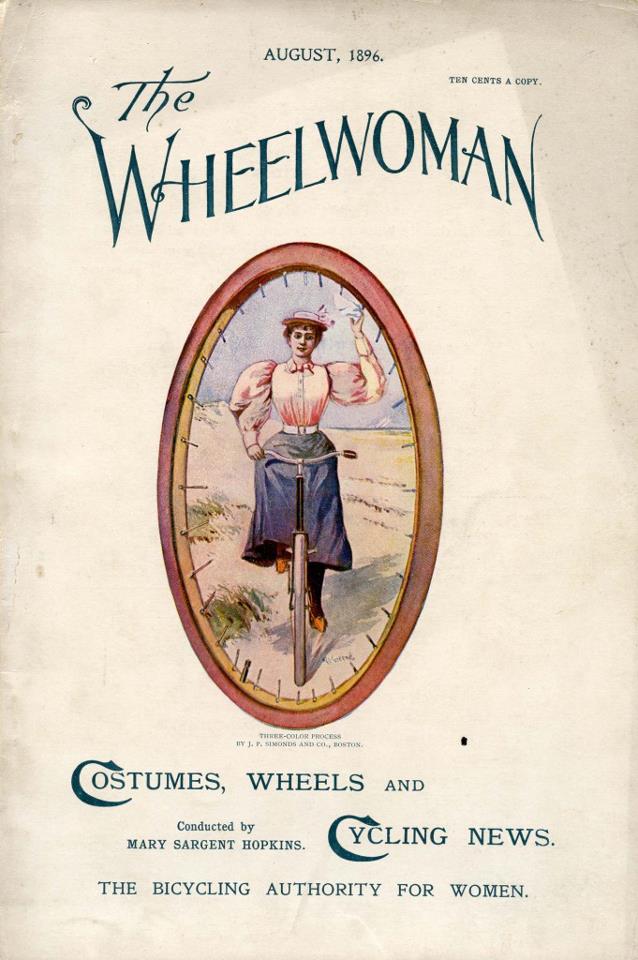

Women’s (Bike) History: Mary Sargent Hopkins

Miss “Merrie Wheeler” was a cautious pioneer by modern standards. Mary Sargent Hopkins, who became known by her penname “Merrie Wheeler,” established her magazine The Wheelwoman in 1895 in Boston. At the time — the heyday of the U.S. bicycling boom — Hopkins was the face of women on bicycles. Before establishing The Wheelwoman, Hopkins was published in Bicycling World and L.A.W. Bulletin, New England Kitchen Magazine and Good Housekeeping, among other publications.

Miss “Merrie Wheeler” was a cautious pioneer by modern standards. Mary Sargent Hopkins, who became known by her penname “Merrie Wheeler,” established her magazine The Wheelwoman in 1895 in Boston. At the time — the heyday of the U.S. bicycling boom — Hopkins was the face of women on bicycles. Before establishing The Wheelwoman, Hopkins was published in Bicycling World and L.A.W. Bulletin, New England Kitchen Magazine and Good Housekeeping, among other publications.

Her cycling journalist contemporary, Ida T. Bell, wrote that Hopkins’ “name has become a household word wherever the bicycle is ridden,” according to a forthcoming book by historian Lorenz Finison. Hopkins was a champion of women’s health, and much of that focused on outdoor recreation.

“The wheel is today the greatest emancipator extant for women — women who are longing to be free from nervousness, sick-headache, and a train of other ills,” Hopkins wrote, according to Finison. “Indeed the bicycle for women deserves to rank with the greatest inventions of the century.”

And while Hopkins identified as a women’s health advocate and bicycle enthusiast, she also believed a woman’s role was a domestic one. Her better health, she argued, would enable her to fulfill her domestic duties with more vigor.

Finison writes of this common-held belief at the time: “Despite much emancipatory language, The Wheelwoman espoused conservative notions of femininity that coexisted during the bicycle craze of the 1890s. Hopkins advocated gradual changes, comforting her middle class readers. The New Woman of Hopkins’ cycling imagery remained assuredly feminine. But she also had the capacity to reform men, and the world.” Though there was a small but growing movement to reform women’s dress, Hopkins didn’t subscribe to this notion.

After initially decrying any type of dress reform, she ultimately endorsed women wearing “short skirts” (about 4 to 8 inches from the ground), instead of the traditional floor-length garb, for bicycling. Much unlike our previous profile of Amelia Bloomer, Hopkins was averse to all things “bloomer.”

Instead she wrote: “It has made my heart sore to see the women who have been putting on knickerbockers, riding the scorching with the men.” But at the time, Hopkins played the important role of happy medium between two often-quarreling sides. “For opponents of women’s rights, the bicycle exemplified the physical and moral dangers ensuing from any changes in the female condition,” Finison writes. “Mary Sargent Hopkins… produced an image of the female cyclist that was a compromise between the poles of this debate… She ingeniously described the New Woman as free yet morally constrained, athletic yet feminine, strong yet yielding, and not subjugated yet serving men.”

Be sure to check back tomorrow for our next profile in our Women’s (Bike) History series!